Iranian Cinema and Revolution: 20 Films, Series and Documentaries to Understand Iran Today

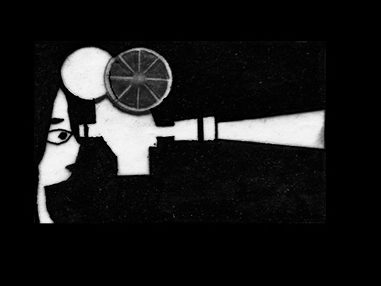

Between Iranian cinema and revolution, the same question keeps returning: how do you film when authority wants to control bodies, speech and images?

Iranian cinema tells the story of a country in permanent tension between authority and freedom.

Through twenty essential films, this dossier sets out to understand how Iranian filmmakers translate anger, memory and disobedience into images.

The death of Mahsa Amini, on September 16, 2022, changed the way these works are read. Older images illuminate the weariness of a society under constraint; newer ones register a historic rupture. Iranian cinema functions like a sensitive archive: it records silences, fear and the courage of ordinary lives.

Filming in Iran demands a choice. Every shot commits the responsibility of the person framing it, the subject being shown, and what is being exposed. This pressure forges a specific kind of writing, built on ellipses, metaphors, restrained gestures. Prohibition becomes a language; censorship, a driver of invention.

Since the Islamic Revolution, Iranian filmmakers have invented forms to outmaneuver surveillance. Their films root themselves in reality while searching for a way to reveal its truth. The viewer discovers a country where speech circulates differently, where the intimate becomes political, and where the act of filming already constitutes a position.

Iranian Cinema and Revolution: Historical Landmarks

Before we move into the works, a chronological reminder is necessary.

Iranian cinema does not move in a straight line. It reinvents itself with every political crisis, depending on the freedoms of the moment and the prohibitions imposed by power. These dates offer a key for reading:

1979 – Iranian Revolution

The fall of the Shah transforms both society and artistic production. The Islamic Republic establishes a state morality, frames permissible subjects, and controls images of women, the street, couples. Filmmakers reinvent their language. Symbol, silence and allusion replace direct realism.

This period lays the foundations of an aesthetic of detour. Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi, 2007) offers a retrospective reading of it. Through childhood, Satrapi translates the political entering the intimate: the way you dress, love, listen to a song becomes an act of resistance.

1980–1988 – Iran–Iraq War

The conflict forges a collective memory of loss and courage. War places fear at the heart of daily life and turns youth into premature witnesses. The Siren (La Sirène, Sepideh Farsi, 2023) restores its trace through a teenager in Abadan. Animation gives flesh back to a generation marked by waiting, scarcity and the promise of a suspended future.

War becomes a school of silence. This trauma then irrigates Iranian cinema as a whole: a culture of contained looking, cautious speech, and memory passed on in a low voice.

2009 – Green Movement

Hope for reform, then repression, transforms public speech. The street closes down, the home becomes a place of debate, the justice system a stage for truth. Taxi Tehran (Taxi Téhéran, Jafar Panahi, 2015) captures society from the driver’s seat; A Separation (Une séparation, Asghar Farhadi, 2011) observes the moral fracture of a country through a domestic trial.

Politics takes root in the ordinary. Filmmakers shoot conversation, doubt, shame. This decade installs a cinema of daily life under tension, where every silence expresses disagreement.

2019 – Social Uprisings

The economic crisis and a rise in fuel prices bring a diffuse anger to the surface. Society suffocates; fear turns into collective exhaustion. Tehran Law (La Loi de Téhéran, Saeed Roustayi, 2019) offers a striking metaphor: the “war on drugs” becomes the portrait of a state saturated by its own violence.

Police stations, corridors, crowds: everything breathes confinement. Roustayi films Iran like an organism under pressure. This climate of suffocation prepares the uprisings to come.

2022 – Death of Mahsa Amini

On September 16, 2022, Mahsa Amini’s death becomes a moral turning point. The slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” turns revolt into a collective horizon. Cinema, long forced to work around reality, now looks it in the face.

Holy Spider (Ali Abbasi, 2022) examines moral violence as a social system. Tatami (Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Guy Nattiv, 2024) shows control over the female body reaching into international sport. Both films mark a decisive evolution: fear changes sides, and the gaze becomes frontal.

2024–2026 – The Emergence of a Cinema of Confrontation

A new generation of films asserts itself, shot in urgency or made from exile. Their authors turn anger into a visual language. The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Les Graines du figuier sauvage, Mohammad Rasoulof, Cannes 2024, Special Jury Prize) and It Was Just an Accident (Un simple accident, Jafar Panahi, Palme d’Or Cannes 2025) embody this pivotal moment.

Rasoulof links the family sphere to the revolution underway; Panahi interrogates memory and justice. These works articulate fiction and reality with unprecedented intensity. They announce a cinema of recovered speech, of confrontation assumed.

These dates structure the reading of the entire corpus. They remind us that politics first inscribes itself in gestures: a look, a closed door, a silence. Iranian cinema works like a radiography of society. Each work extends history by other means.

Live-action fiction translates constraint through everyday life — family, justice, loyalty, fear. Animation opens another path: memory, metaphor, confession. It makes it possible to address exile and transmission without risking betraying the living. In this dialogue between realism and allegory lies the full force of contemporary Iranian cinema.

Animated Films: Memory of 1979, War, Taboos, Exile

Animation occupies a singular place in Iranian cinema. It bypasses censorship by creating a symbolic space, capable of saying what a real camera cannot show. It tells memory, prohibitions and collective traumas with a visual freedom that live-action shooting forbids. These films reinvent the relationship between truth and image.

Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi, Vincent Paronnaud) – France release: June 27, 2007

Voices : Chiara Mastroianni, Catherine Deneuve

Award : Jury Prize, Cannes Film Festival 2007

Persepolis follows Marjane, a child in Tehran, from the fall of the Shah to her exile in Europe. Satrapi turns the story of a young girl into the portrait of a nation. The deliberately pared-down black-and-white drawing evokes the clarity of a memory engraved in fear and waiting.

The film describes politics as an intimate force: wearing the veil, listening to music in secret, the way you walk become acts of resistance.

In today’s context, Persepolis retains immediate relevance. It reminds us that political consciousness often begins in childhood, when power enters the home. Satrapi builds a universal coming-of-age story and offers a female reading of Iranian history, still central after 2022.

The Siren, Sepideh Farsi – animation, France release: June 28, 2023

Award : Best Original Music Prize, Annecy Festival 2023

In Abadan, in 1980, the Iran–Iraq war traps the population inside a besieged city. Omid, fourteen, looks for a way out.

The Siren stays with his gaze, between curiosity, fear and tenderness.

Farsi reconstructs a collective memory. She films the siege not as a heroic episode, but as a permanent state of survival. Animation restores light, heat, dust, the slow time of war.

Today, the film works as a reflection on how the logic of siege persists in Iranian society: constant vigilance, an unstable relationship to the world. Farsi combines documentary precision with the softness of remembrance, creating a cinema of inner resistance.

Tehran Taboo, Ali Soozandeh – rotoscoped animation, 2017

Cast : Elmira Rafizadeh, Zahra Amir Ebrahimi

Selection : Annecy Festival, many European festivals

Tehran Taboo interweaves the destinies of three women and a young musician in the Iranian capital. Each tries to escape a morality that polices bodies and desires.

Soozandeh uses rotoscoping (animation traced from filmed images) to enter places forbidden to a real camera. This technical freedom creates a paradoxical truth: the more the city is drawn, the more real it seems.

The film explores Iranian society as a theater of prohibitions. Religion, reputation and fear form a system of mutual observation. The state governs, but society prolongs its surveillance.

Today, Tehran Taboo resonates with contemporary debates on women’s freedom, social control and the double life imposed on an entire generation. Animation becomes a form of clandestine cinema: a space of speech where you can finally breathe.

Iranian animation invents another form of realism. It makes memory visible without endangering those who carry it. Satrapi, Farsi and Soozandeh belong to the same lineage: those who film society through metaphor, childhood, dream, in order to reveal its scars.

This cinema builds an active memory: it turns recollections into tools for understanding the present. After 2022, these films reappear as archives of ordinary resistance, the kind that comes before slogans.

Iranian Cinema and Revolution: Filming Under Constraint (2009–2019)

Between 2009 and 2019, Iranian cinema explores constraint as raw material. Cameras settle in apartments, taxis, police stations. Filmmakers turn prohibition into an engine of invention. Reality circulates in the gaps: a conversation in a car, a couple’s argument, a trial that overflows.

This cinema of everyday life, often made under precarious conditions, captures society through gestures and silences. Speech becomes the site of politics.

Taxi Tehran – Jafar Panahi (Golden Bear, Berlinale 2015)

Award : Golden Bear, Berlinale 2015

Jafar Panahi, under house arrest, mounts a camera on a taxi dashboard and drives through Tehran. Passengers get in, talk, laugh, complain. Each ride composes a fragment of the country.

The taxi becomes a roaming studio. Panahi films how words circulate: between official injunctions and free speech, a fragile space opens. The film documents the city in real time and turns conversation into a political performance.

Today, Taxi Tehran retains rare documentary power. It shows how Iranian society constantly invents spaces of freedom: a vehicle, a camera, an exchange are enough to create a place of resistance.

A Separation – Asghar Farhadi (Golden Bear 2011, Oscar)

Awards : Golden Bear, Academy Award for Best International Feature Film

Farhadi places his camera inside a family in crisis. A couple splits up, a caregiver falls, a judge steps in. Every word produces a moral consequence.

The film explores Iranian society through the prism of responsibility and judgment. Justice, religion and social class intersect in a suffocating tangle.

In today’s context, A Separation illuminates the moral structure that still underpins power: fear of scandal, reputation, shame. Farhadi films a country where truth depends on status, gender and the gaze of others. The film continues to operate like an ethical radiography of the country.

Tehran Law (original title: Metri Shesh Va Nim) – Saeed Roustayi

Award : Grand Prix, Reims Polar 2021

Cast : Payman Maadi, Navid Mohammadzadeh

Roustayi films the “war on drugs” as a state machine. Police stations overflow, prisons fill up, the street becomes a labyrinth of procedures.

The film captures the density of the city, its organized chaos, its speed. It places the camera in the noise of corridors, in the dust of cells.

Under the guise of a crime thriller, Tehran Law depicts a society managed by fear. Every arrest sustains the illusion of order. Roustayi shows how repression becomes routine and how control manufactures collective exhaustion.

Shot before the 2022 uprising, the film already carries its signs. The tension accumulated in its images foreshadows the anger to come.

Black Market (original title: Koshtargah, international title: The Slaughterhouse) – Abbas Amini

Award : Jury Prize, Reims Polar 2021

Cast : Amirhosein Fathi, Mani Haghighi, Baran Kosari

Amir returns from Europe and finds a country shaped by hustling, trafficking and lies. The underground economy replaces institutions. Characters constantly slip between legality and survival.

Amini films this gray zone with clinical precision. The direction refuses emphasis and stays with gestures: sell, hide, lie, start again.

Black Market reveals a society where compromise becomes a way of life. This culture of arrangement prepares the ground for revolt: when nothing rests on trust anymore, the need for truth becomes political.

A Hero – Asghar Farhadi (Grand Prix Cannes 2021, ex aequo)

Award : Grand Prix, Cannes 2021*

Cast : Amir Jadidi, Mohsen Tanabandeh

Farhadi continues his moral investigation. A man is released from prison, returns a bag of gold found by chance, and becomes a public symbol. Opinion elevates him, then destroys him.

The film questions the manufacture of heroes, the speed of judgments, the force of narratives. In a society saturated with social surveillance, reputation becomes a form of control.

A Hero sheds light on the transition toward post-2022 cinema: individual morality collides with collective logic. The group’s gaze acts like an invisible police force.

The Aesthetic Sense of Constraint

Between 2009 and 2019, Iranian cinema develops an aesthetic of the obstacle. Framing becomes a cage, speech a measure of risk, editing a way to escape censorship.

Panahi, Farhadi, Roustayi and Amini build a coherent corpus: each turns constraint into method. The fixed shot, the closed room, the fragmentation of narrative produce an effect of truth.

This cinema shows how a society lives under tension and how art records that pressure.

These films form a collective archive of daily life under surveillance: a geography of waiting, compromise and courage.

2022–2026: Iranian Cinema and Revolution — The Post-2022 Shift

From 2020 onward, Iranian cinema enters a period of rupture. Filmmakers shoot a country waking up, a society breaking with resignation. Reality crosses the screen. Stories take the street, fear circulates between walls, disobedience becomes language.

These works mark a turning point: they assert direct confrontation, controlled anger and the will to record a people’s transformation.

There Is No Evil – Mohammad Rasoulof (2020)

Award : Golden Bear, Berlinale 2020

Cast : Ehsan Mirhosseini, Kaveh Ahangar, Mohammad Valizadegan

Rasoulof builds four stories linked by a single thread: responsibility in the face of the death penalty. Each follows an individual confronted with obedience and fear. The state imposes punishment, but individuals perpetuate it.

The mise-en-scène rests on the tension of gestures: opening a door, making tea, waiting for an order. And the film makes the banality of power visible.

In the post-2022 context, There Is No Evil illuminates the continuity of control. Rasoulof films violence not as an event, but as a collective system. The film becomes a mirror of a society where submission is confused with survival.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig – Mohammad Rasoulof (Cannes 2024)

Award : Special Jury Prize, Cannes Film Festival 2024

France release : September 18, 2024

Cast : Setareh Maleki, Soraya Khajeh

Rasoulof continues his exploration of fear, but turns it into political energy. The film links the intimate and the collective. A high-ranking official father, his two daughters and their mother experience the revolution from inside the home. The household becomes a laboratory of crisis.

And the filmmaker inserts real images from the 2022–2023 protests. The border between fiction and documentary dissolves. The father embodies the state, the daughters the youth demanding another world, the mother the awareness of an irreversible fracture.

This film describes the passage from a silent society to a society standing up. Rasoulof films fear as a mechanism that malfunctions, an authority collapsing under the weight of its lies. The film reads as an immediate chronicle of the revolution in progress.

It Was Just an Accident – Jafar Panahi (Palme d’Or 2025, film selected by France for the 2026 Oscars)

Awards : Palme d’Or, Cannes 2025

France’s official selection for the 2026 Oscars

France release : October 1, 2025

Cast : Navid Mohammadzadeh, Taraneh Alidoosti

Panahi returns after several years under a ban on filmmaking. The film follows a former lawyer haunted by a miscarriage of justice. His investigation leads him to reopen a case filed away as an “accident.”

Panahi turns this intimate narrative into a meditation on memory and responsibility. Faces carry the fatigue of a country where truth costs dearly. Every shot explores doubt: doubt in justice, in the gaze, in the witness.

The title, It Was Just an Accident, condenses the rhetoric of power. What the state erases, the film revives. Panahi shows how Iranian society relearns how to name facts.

His work becomes a gesture of insistence: to record, to understand, to persist.

What Iranian Cinema Says Differently Today (Post-2022)

Before 2022, Iranian cinema often worked constraint through detour.

Since Woman, Life, Freedom, it has made three major shifts:

- From off-screen to confrontation (Tatami, It Was Just an Accident).

- From moral conflict to generational conflict (The Seed of the Sacred Fig).

- From individual survival to disobedience (sport, exile, narratives of direct collision with the state apparatus).

This is not a change of style. It is a displacement of risk.

Women, Bodies, Disobedience: The Heart of Iranian Revolutionary Cinema

Since 2022, women have moved to the center of Iranian narrative. Cinema records this shift with unprecedented intensity. The female body, long an object of control, becomes an instrument of revolt. The home, sport and culture turn into political terrain.

Three recent works embody this turning point: Holy Spider, Tatami and Reading Lolita in Tehran (Lire Lolita à Téhéran). Each describes a territory where women’s speech asserts itself against fear.

Holy Spider – Ali Abbasi (2022)

Award : Best Actress Prize – Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Cannes 2022

Cast : Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Mehdi Bajestani

France release : July 13, 2022

In the holy city of Mashhad, a man murders sex workers to “purify” the city. A journalist investigates and confronts a society that celebrates the killer as a vigilante.

Ali Abbasi builds a chilling thriller where morality turns against justice. The camera follows the journalist through an environment saturated with religious discourse and hostile stares.

Zar Amir Ebrahimi, exiled from Iran, embodies a heroine without illusions, but without fear. Holy Spider dissects how an ideology turns violence into virtue.

In the context of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, the film acts as a mirror: it shows how domination operates through daily gestures, and how bearing witness becomes a political act.

Tatami – Guy Nattiv & Zar Amir Ebrahimi

Award : Audience Award, Venice Film Festival 2023 (Orizzonti section)

France release : September 4, 2024

Cast : Arienne Mandi, Zar Amir Ebrahimi

The film takes place during the Judo World Championships. Leila, an Iranian athlete, is ordered to withdraw to avoid facing an Israeli opponent. Her coach, Maryam, tries to protect her while resisting threats from Tehran.

Tatami places tension in every phone call, every breath before a fight. Sport becomes a metaphor for political control. The female body, monitored from afar, embodies the fight for dignity.

Zar Amir Ebrahimi films courage without emphasis: the camera holds on the face, sweat, breath.

Within the landscape of contemporary Iranian cinema, Tatami symbolizes disobedience in motion. It links women’s struggle to a universal grammar: choice, risk, inner freedom.

Reading Lolita in Tehran (Eran Riklis) – The Revolution of Minds Before the Street

Adaptation : from Azar Nafisi’s memoir

Cast : Golshifteh Farahani, Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Mina Kavani, Bahar Beihaghi

France distributor : Metropolitan FilmExport

France release : March 26, 2025 • Running time: 1h48

In a discreet Tehran apartment, professor Azar Nafisi gathers a small group of students to read banned novels. Around Lolita, The Great Gatsby and Madame Bovary, these women recover an inner language.

Riklis films reading as a political act. Faces lean over pages, voices free themselves, thought circulates. The closed room becomes a space of emancipation.

Reading Lolita in Tehran shifts revolution from the street to the mind. It describes the birth of an individual consciousness against a collective norm.

The film works as a metaphor for artistic creation: reading, thinking, imagining are already gestures of resistance. In the wake of Satrapi and Ebrahimi, it affirms culture as a quiet weapon against erasure.

A Cinema Carried by Women’s Voices

Since 2022, Iranian filmmakers and actresses have multiplied projects in exile. Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Golshifteh Farahani, Mina Kavani and Sepideh Farsi drive a worldwide artistic movement. Their work turns pain into narrative, fear into vision.

Their cinema shifts the struggle into visibility. Every shot, every gesture, every word opposes presence to power. These films build a memory of women’s resistance: not heroic, but relentless.

Documenting the Revolution: Stating the Facts Without Aestheticizing Them

Iranian and European documentaries on Iran play an essential role. They fix chronology, restore voices, anchor reality. These films give collective memory its skeleton. They build an immediate history of the uprising, at human scale.

Woman, Life, Freedom – An Iranian Revolution

Directing : Claire Billet & Mohamad Hosseini

Initial broadcast : 2023

Access : ARTE Campus / ARTE Boutique (depending on periods)

This film, produced by ARTE, assembles clandestine footage shot during the first weeks of the 2022 uprising. Mobile phones, testimonies, faces filmed from a distance create a raw, direct account.

The filmmakers build a rigorous edit: facts follow the chronology of demonstrations, from Mahsa Amini’s death to the first executions.

Woman, Life, Freedom – An Iranian Revolution restores the strength of the collective. Speech circulates despite fear; faces appear despite threat. The documentary reminds us that the Iranian revolution also unfolds through control of images, through the ways of showing and sharing.

This work functions as a counter-archive: it protects a people’s memory against organized erasure.

We, Iran’s Youth (Nous, jeunesse(s) d’Iran)

Directing : Solène Chalvon-Fioriti

Production : Chrysalide Production, Elephant Doc

Broadcast : France Télévisions, 2024

Carried by witnesses under 25, Solène Chalvon-Fioriti’s film explores the present tense of Iranian youth. The director collects the stories of a generation growing up under permanent control.

Thanks to face-anonymization technology, participants keep their emotional identity without risking their safety. Eyes remain intact; expressions breathe.

The documentary shows a plural youth, between disillusionment and creative energy. The country appears as a moral laboratory: each young person learns to live with fear, dreams, solidarity.

We, Iran’s Youth joins the lineage of works that turn testimony into political art. It captures speech where it forms: in bedrooms, streets, screens.

ARTE: A Central Role in the Circulation of Iranian Cinema

The Franco-German channel plays a structuring role in the circulation of Iranian works in Europe. It juxtaposes fiction, documentaries, short formats and interviews, creating a unique editorial coherence.

Through its platform, ARTE offers free access to a fragile heritage. Films, series and interviews allow approaches to be compared, narratives to be cross-read, and critical reading to be built.

In the European media landscape, ARTE acts as a go-between. It turns spectators’ curiosity into political awareness.

Happiness (Iran/France) — mini-series (15 × 6 min)

Online on ARTE : 2021

Access : arte.tv (free)

Official Selection, Séries Mania 2021 – Short Formats Competition

Tehran today. Shadi, 17, runs away with friends to escape routine and family pressure. Fifteen six-minute episodes compose a miniature odyssey through contemporary Iran.

Takavar films youth as a moving territory. Images designed for Instagram circulate like fragments of freedom.

Happiness works as an aesthetic laboratory: fast editing, direct dialogue, an electric soundtrack. The film translates the energy of a generation moving forward despite surveillance.

The Actor (Iran) — series (26 × 52 min)

Availability : ARTE.tv, available until 2026

Cast : Navid Mohammadzadeh, Ahmad Mehranfar, Hasti Mahdavi

Award : Grand Prix, International Competition, Séries Mania 2023

Two Tehran actors make a living through improvised performances, paid for by clients who want to manipulate reality. Acting becomes a form of survival.

The series explores the border between truth and lies, fiction and power. Nima Javidi turns staging into a metaphor for life under surveillance.

The Actor extends contemporary Iranian cinema: it captures society through masks, performance, doubles. Theater becomes a tool of adaptation. Survival becomes art.

Conversation with Actress Zar Amir

ARTE broadcast : 2023

This interview gives a face to resistance. An actress exiled since 2008, she recounts her journey from censorship to international recognition.

She describes the double life of an Iranian artist: working abroad while remaining under threat. Her words connect films to the reality of danger.

The interview clarifies what fiction suggests: the persistence of fear, the solitude of exiles, the price of visibility.

It reads like a lesson in quiet courage. Behind every role, a woman builds a space of survival and dignity..

The Documentary Sense of Revolution

Documentaries and series about Iran build another form of engagement. They refuse to aestheticize suffering and privilege factual rigor.

Billet, Hosseini, Chalvon-Fioriti and Javidi create a new grammar: to film is to archive the present. Their images compose an immediate memory, a living map of revolution.

These works show the power of the collective and the continuity of courage. They complement fiction by giving it a concrete foundation.

Exile: Another Stage for Iranian Revolutionary Cinema

Exile now forms the other side of Iranian cinema. It is not an escape, but a condition of creation. For many artists, leaving means continuing to film, write, act. Far from the country, they rebuild a space where speech remains free and memory circulates.

Diaspora cinema becomes a parallel cartography: an Iran dispersed, polyglot, female, conscious of its history.

Zar Amir Ebrahimi: The Actress as Resistance

Zar Amir Ebrahimi, revealed to a wider audience by Holy Spider and co-director of Tatami, embodies a central trajectory. Her path, between exile and recognition, symbolizes the persistence of an independent Iranian voice.

Exiled after a scandal fabricated by the regime, she rebuilt her career in France and Denmark. Her artistic choices show rare coherence: each role interrogates morality, shame and visibility.

In Holy Spider, she investigates a world that venerates male violence. In Tatami, she films fear at a distance. Her work links the intimate and the collective.

Zar Amir Ebrahimi represents a generation of artists who turn injury into method. Her acting, sober and taut, becomes a form of living archive: a body that bears witness without pathos.

Golshifteh Farahani: Freedom as an Aesthetic Horizon

Based in Paris since 2008, Golshifteh Farahani embodies continuity between Iran before and Iran elsewhere. Her roles, from Body of Lies to Extraction, weave a dialogue between cultures.

In Reading Lolita in Tehran (Eran Riklis, 2025), she returns to the language and context of her origins. She plays a woman who resists through thought, a role that extends her own trajectory as an exile.

Farahani makes physical presence a political weapon. Every appearance on screen claims the right to exist without a veil, without justification. She builds a space of active beauty, a visible freedom.

Mina Kavani: Visibility as a Battle

Actress and activist, Mina Kavani is among the most committed faces of the Iranian scene in exile. Her path connects theater, cinema and the defense of artistic freedoms.

Present in Reading Lolita in Tehran, she embodies transmission between generations of exiles. Kavani speaks without detour: culture remains a field of resistance, even from afar.

Her engagement reminds us that exile does not sever the link to Iranian society; it reformulates it.

Marjane Satrapi: Memory, Humor, Transmission

Author of Persepolis, Satrapi remains the pioneer of Iranian diaspora cinema. Her work combines drawing, autobiography and political history.

Her influence remains central: she opened the way for a generation of directors who film exile without nostalgia.

Satrapi transforms recollection into collective narrative. Her graphic style, clear and frontal, defined an aesthetic of memory: black-and-white as a durable trace of courage.

Mohammad Rasoulof: Speech as an Act of Survival

Forced into exile in 2024, Mohammad Rasoulof represents the figure of the filmmaker who continues his work despite threat.

His films — There Is No Evil and The Seed of the Sacred Fig — extend the Iranian revolution through mise-en-scène.

Rasoulof conceives creation as a vital gesture. Exile gives him a new space for speech, but also the responsibility to testify. His approach echoes that of writers of political exile: filming becomes a way of remaining present in the country.

Bahman Ghobadi: Cinema of Borders

Born in Iranian Kurdistan, Bahman Ghobadi films the country’s margins. His masterpiece, Turtles Can Fly (Les Tortues volent aussi, 2005), unfolds in a mined zone on the Iraqi border.

The film shows children collecting mines to survive. War becomes an environment, not an event.

Ghobadi installs a cinema of territory: he reveals ethnic and social fractures ignored by the capital. His gaze expands the map of Iranian cinema.

Through him, exile merges with identity. His characters inhabit edges, passages, uncertain zones.

Exile as Aesthetic and as Language

Exile is not limited to geography. It becomes a form of writing. Iranian filmmakers dispersed across the world build a cinema of distance.

Their gaze connects Tehran, Paris, Berlin, Los Angeles. This circulation produces a fluid, multicentered memory.

Their work asserts a clear idea: Iranian culture belongs to those who keep it alive, wherever they are. Every film made in exile acts like a letter addressed to the country.

Beyond Tehran: Expanding the Cartography of Revolution

To avoid a capital-centered reading, it is necessary to include films that shift the gaze toward provinces, borders, minorities. Protest has never had only one face.

Turtles Can Fly – Bahman Ghobadi

Awards (selection) : Special Mention, Youth Jury – Berlinale 2005; Peace Film Award – 2005; Golden Shell – San Sebastián 2004

Set in a Kurdish region on the Iraqi border, the film follows a group of children collecting mines to survive. War becomes landscape, not event.

Bahman Ghobadi films ruins, hills and children’s faces as permanent witnesses to the conflict. His camera seeks neither pathos nor beauty; it exposes the political geography of a world condemned to vigilance.

Seen today, Turtles Can Fly reveals the territorial depth of the Iranian story. Iran filmed from its margins better tells its fractures: ethnic, social, economic. Ghobadi inscribes revolution in the ground, in mined earth, in daily survival.

Series: Iran Through the World’s Gaze

Tehran — espionage series (seasons 1–3)

Created by: Moshe Zonder, Dana Eden, Maor Kohn

Main director: Daniel Syrkin

Production / distribution: Apple TV+

Languages: Persian, Hebrew, English

Season 3: from January 9, 2026 (Apple TV+)

Main cast : Niv Sultan (Tamar Rabinyan), Shaun Toub (Faraz Kamali), Shila Ommi (Nahid), Glenn Close (season 2), Hugh Laurie (season 3)

Tamar Rabinyan, an Iranian hacker and Mossad agent, infiltrates Tehran under a false identity. What begins as a technical mission becomes a spiral of lies, crossed loyalties and total surveillance.

The series offers an external reading of the country, built on the codes of the Western thriller. It projects an image of Tehran saturated with tension, fear and double games.

Tehran does not aim for social realism, but its success underscores a major fact: the Iranian capital has become a global imaginary, a symbol of opacity and danger.

Watching the series with critical distance helps measure how international fiction reinterprets Iranian political stakes through the prism of suspense and paranoia.

Recommended Viewing Order

This 20-step path crosses forty years of Iranian history through its images. It links the intimate and the political, memory and disobedience, the country and the diaspora. Each work sheds light on a period, a fracture or a face of power.

-

Persepolis (2007) – childhood and the birth of political consciousness

-

The Siren (2023) – memory of the Iran–Iraq war

-

Tehran Taboo (2017) – double morality and a society under control

-

A Separation (2011) – moral fracture and social justice

-

Taxi Tehran (2015) – monitored speech, filmed speech

-

Tehran Law (2019 / France release 2021) – social state and structural violence

-

Black Market (2022) – parallel economy and moral survival

-

A Hero (2021) – reputation and manipulation of morality

-

There Is No Evil (2020) – obedience, guilt, responsibility

-

Turtles Can Fly (2005) – war and Kurdish marginality

-

Happiness (2021) – youth, movement and disenchantment

-

Woman, Life, Freedom – An Iranian Revolution (2023) – facts, images and chronology

-

We, Iran’s Youth (2024) – the voice and courage of a generation

-

The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024) – generational rupture and the power’s fear

-

Holy Spider (2022) – systemic violence and social fanaticism

-

Tatami (2024) – female disobedience and regime pressure

-

Reading Lolita in Tehran (2025) – revolution of minds before the street

-

It Was Just an Accident (Palme d’Or 2025) – memory, justice, after censorship

-

Conversation with Actress Zar Amir (2023) – exile speech and the cost of visibility

-

Tehran (Apple TV+ series, 2020–2026) – paranoia and the world’s perception of Iran

Critical Reading

From Persepolis to It Was Just an Accident, Iranian cinema builds a layered collective memory.

Animated films open the story (Satrapi, Farsi), family dramas (Farhadi, Panahi) translate constraint, social thrillers (Roustayi, Abbasi) expose its violence, and recent works (Tatami, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, It Was Just an Accident) film revolt in the present tense.

Documentaries and series (Woman, Life, Freedom, Happiness, Tehran) finally fix the facts and extend reflection.

This path makes visible a revolution, an aesthetic and moral mutation that transforms how the world looks at Iran.

Conclusion: What Iranian Revolutionary Cinema Reveals

Iranian revolutionary cinema forms a living archive.

Twenty works, twenty ways of telling the same tension: how to live, love and create in a society saturated with control.

Each decade has invented its language:

-

the 1980s, the decade of war, gave rise to a memory of siege and mourning (The Siren, Turtles Can Fly);

-

the 2000s, marked by the repression of the Green Movement, shifted politics into the intimate (A Separation, Taxi Tehran);

-

the 2010s, the decade of disillusion, showed justice as a theater of power (Tehran Law, Black Market);

-

since 2022, cinema finally films disobedience in full view (Holy Spider, Tatami, The Seed of the Sacred Fig, It Was Just an Accident).

This cinema composes a moral radiography of the country.

Each director chooses a survival strategy: detour, allegory, exile, or frontal confrontation.

-

Panahi turns a car into a space of provisional freedom.

-

Farhadi films morality as a labyrinth with no exit.

-

Rasoulof unfolds the machinery of obedience until it breaks.

-

Roustayi lays bare the logic of a state that manages misery as a resource.

-

Satrapi, Farsi, Soozandeh or Riklis entrust animation and reading with the task of preserving memory.

These films show a country that speaks through its filmmakers. They make Iran exist beyond official discourse. Their power lies in precision: a look, a place, a situation.

Watched together, they trace the slow transformation of a society: from submission to speech, from fear to awareness, from silence to transmission.

This cinema does not merely accompany the Iranian revolution: it is its soundtrack, its memory and its pedagogy.

FAQ – Iranian Cinema Revolution

Which films should you watch to understand the current Iranian revolution?

The Seed of the Sacred Fig, It Was Just an Accident, There Is No Evil, Tatami, Holy Spider and the documentary Woman, Life, Freedom – An Iranian Revolution.

Which films show Iran beyond Tehran (provinces, minorities)?

Turtles Can Fly (Bahman Ghobadi) and The Siren (Abadan, Iran–Iraq war).

Where can you watch Iranian films today?

ARTE / ARTE Boutique, theaters, Canal+ VOD, and Apple TV+ .

Call to the Community

And you, which Iranian film has affected you the most?

Share your discoveries, your emotions, your anger.

Comment, tag your favorite cinephiles, and subscribe to the Movieintheair newsletter to follow new perspectives coming out of Iran.

To learn more: Falafel Cinéma : Israeli cinema and Iran