Why this interview?

With Mama,, presented at Cannes 2025, Israeli director Or Sinai delivers a powerful debut feature, inspired by a deeply personal experience: the arrival of a migrant caregiver in her parents’ home. From that encounter emerged a poignant work — intimate and grounded — filmed close to the body, to desire, and to the silence of Mila, a Polish caregiver caught between distance, absence, and social indifference.

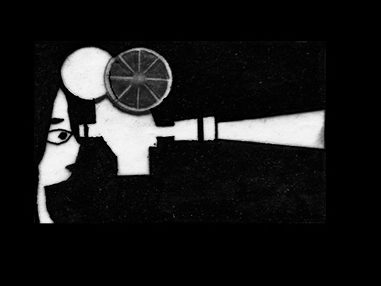

Through five questions, Or Sinai challenges our stereotypes, exposes invisible hierarchies, and crafts a sensory and political portrait. A cinema of perspective that places feminine subjectivity at the heart of every frame and artistic choice — making Mama far more than a social drama. It is an inner odyssey.

Mama puts a woman’s perspective at the center—how did you build Mila’s gaze and subjectivity throughout the film?

I began writing this story when a migrant caregiver came to work at my parents’ home. A bulldozer dug a deep hole in the ground to build an underground room for the new woman in their house. In those first days, I was struck by the strange dynamic between my parents and the woman who had suddenly become part of the household — and yet not truly part of it. It felt like they were all engaged in some kind of silent performance.

I was fascinated by her, and very quickly we realized we are almost the same age and started talking to each other openly. She told me stories about her family back home, and about her “temporary” lover — a relationship from her temporary life, far from home. Her stories amazed me, and they inspired the script. I conducted deep research into migrant women workers who had left distant homes and built temporary identities within the households where they worked. And that’s why, from the very beginning, it was Mila’s point of view that captivated me and made me want to tell this story. I wanted audiences to fall in love with her the way I fell in love with the women I met.

Throughout the entire process, it was important for me that viewers experience Mila from the inside — to follow her emotional journey. So the screenplay was written entirely from her perspective. There isn’t a single scene — not even a moment — without her on screen. That approach carried over into the cinematography as well: the camera always stays close to her, allowing the audience to experience everything through her eyes.

What did you want to reveal or challenge about how society looks at migrant and “invisible” women?

I wanted to shed a new light on chachters from the outskirts of society. When I met Olga, the woman working for my parents, I realized that I, too, had certain expectations about how a migrant worker probably live her life. But her stories constantly surprised me and shattered the stereotypes I had in my mind.

We’re used to seeing migrant women as pitiful figures who sacrificed their lives for their children — but in this film, I wanted to tell a more complex story.

Yes, Mila in some ways has sacrificed her life, but she’s also gained things she couldn’t have accessed any other way. It’s true that she suffers under the distorted social hierarchy we all live in, but she also lives a life full of passion. She has a sex life, and she experiences longing, pleasure, anger, and hope — just like anyone else. I wanted to challenge the way society makes these women invisible by reducing them to their function. Mila isn’t just a caregiver — she’s a full human being with desires, contradictions, and her own inner world. Through her story, I hoped to invite the audience to see migrant women not as background characters in someone else’s life, but as protagonists in their own.

How did you use the camera and mise en scène to reflect Mila’s inner world, her body, her desire, her resilience?

Mila left her familiar surroundings and relocated geographically in order to build a future that she believed would benefit her family, following her conscience. The environment Mila chose to place herself in plays a major role in the film—it is both the solution and the source of conflict. In the visual interpretation of the script, we aimed to emphasize Mila’s presence within the space, offering an opportunity to experience both the environment and her character authentically, without compromising on a cinematic visual language that conveys information, emotions, and fine details simultaneously, while avoiding repetitive close-ups as much as possible.

We used relatively wide lenses and staged scenes with abundant movement, allowing a single shot to shift and encompass multiple focal distances. This approach created moments where Mila is seamlessly integrated into her surroundings but also detaches herself, moving closer to the lens and allowing the viewer to interpret her emotions more intimately.

Which moment or scene, for you, most embodies the power of the female gaze in Mama?

For me, the most powerful moment is the hospital sequence — I won’t reveal exactly what happens there to avoid spoilers. What I can say is that it’s a moment shared between three women, who are all engaged in a kind of game with each other. Each of them is in the game unwillingly, doing the best she can within impossible circumstances — and yet, it ultimately leads to a painful collapse.

Mila, the protagonist, faces a deep dissonance between her expectations and reality, which pushes her to take an extreme action involving her daughter. In that moment, she uses her own femininity — and her daughter’s — as a tool to achieve what she needs.

What response or recognition from women viewers has meant the most to you?

What’s been really interesting is that every time we screened the film for women, we noticed a clear split. There’s one group of women who deeply identify with Mila — they understand her, and they feel her pain. And then there’s another group who are angry with her, who feel that she goes too far and does terrible things to her daughter.

I think it’s fascinating to open up a conversation between those two perspectives. And more than anything, I’m glad that Mila’s character is complex — she’s not simply “good” or “bad,” she’s human. That kind of emotional and moral complexity is exactly what I wanted to explore.

The most meaningful reaction arrived from Olga herself, who was the inspiration for the story. She was deeply moved and excited to watch the film, and she felt that her story was being told — and that was incredibly meaningful to me. It was a moment of recognition and validation for both of us, and it reminded me why I made the film in the first place: to give voice to women like her, whose lives are so often overlooked or misunderstood.