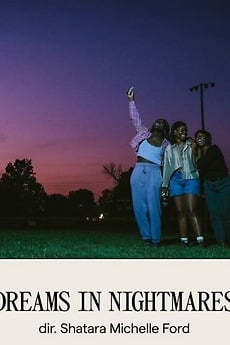

Dreams in Nightmares – A queer road-movie haunted by memory

Seen at the Champs Élysées Film Festival.

Dreams in Nightmares: a different kind of road-movie: no plot, no map, no resolution

Three Black queer women in their thirties set off across the American Midwest to search for a missing friend. But the quest fades into a deeper journey—an interior drift shaped more by silence and tension than by narrative development. Shatara Michelle Ford, previously acclaimed for Test Pattern, departs here from classic dramatic structures to build a fragmented, suspended form of storytelling. Her second feature doesn’t aim for resolution or redemption, but for a livable space.

Absence as narrative structure

The film begins with a disappearance. Lauren—or perhaps Tasha—has chosen to vanish. Z and Kel search for her, without chasing her. They take to the road with Dezi, following no plan, no direction. What they navigate is not geography, but psychic terrain. The rigid highways of the Midwest do not open up the landscape; they confine it. Gas stations, diners, and empty stretches of road form a geography where Black queer bodies remain uninvited, even when they ask for nothing.

Ford doesn’t portray a disappearance; she stages a refusal to remain visible. Lauren escapes not out of despair, but out of necessity. She disappears to protect a self that cannot exist openly. Her retreat becomes a dream—or a nightmare—that the film keeps circling. Z, in turn, is haunted not by the person, but by the ungraspable possibility of connection. What she searches for is not her friend, but a kind of bond that exists beyond identity and trauma. But the dream stalls. The protagonist cannot free herself from the weight of her past. She carries history like a second skin—history she cannot shed, nor narrate.

A film haunted by the legacy of slavery

The film never names slavery. It doesn’t need to. Every frame carries its shadow. The American flag appears only once, fleetingly—and it is stained. That stain says everything. Red, white, and blue cannot conceal the blood of Black people spilled across generations. The legacy of slavery seeps into every silent moment, into every spatial constraint. The American Dream remains inaccessible, a background fiction that these characters never believed in.

Queer love without drama, without martyrdom

Dreams in Nightmares chooses not to center pain. Ford refuses victimhood, refuses catharsis. Queer love here is not a site of struggle—it is a form of presence, of joy, of sensuality. The film celebrates touch, laughter, flirtation. These women don’t survive—they live. The chosen family is not a safe space, but a radical construction, constantly negotiated. Friendship doesn’t heal. It holds, it stretches and it breaks and reforms. Ford films it with precision, without romanticizing, without moralizing.

A sensory film of silence and distance

Cinematographer Ludovica Isidori reinforces Ford’s aesthetic: bodies are framed but never possessed. Light traces the skin but never fetishizes it. The camera follows, never leads. It listens. It waits. Every shot breathes. The sound design avoids sentimentality; music accompanies movement but never dictates emotion. The film creates rhythm without climax, without reward. It invites immersion without guarantee.

A queer independent film that refuses resolution

The film offers no narrative arc. It holds no closure. It proposes a moment—a rupture—and lets us dwell inside it. That formal choice may disorient some viewers. But it is deliberate. Dreams in Nightmares resists the logic of repair. It chooses incompleteness, tension, and fluidity. It trusts its audience to sit with uncertainty.

Dezi’s character remains underdeveloped—less embedded in the central tension between Z and Kel. But the imbalance feels deliberate. It evokes the instability of human connection, the impossibility of total understanding.

A rare film: vulnerable, unresolved, and unafraid

Ford doesn’t explain identity. She doesn’t dramatize trauma, she doesn’t offer representation as consolation. And she builds a space for Black queer life that refuses spectacle. Her camera withdraws from what has been overexposed and lingers where cinema rarely looks: in the friction of silence, in the pauses of intimacy, in the failures of speech.

Dreams in Nightmares magnifies queer love without martyrdom. It sets aside drama to make room for memory, desire, and unfinished dreams. It is a rare film that turns absence into structure, softness into resistance, and silence into a sharpened political gesture.

Festival Selection

Official selection – Champs-Élysées Film Festival 2025, Paris, June 17–23

In competition – American Independent Feature Films