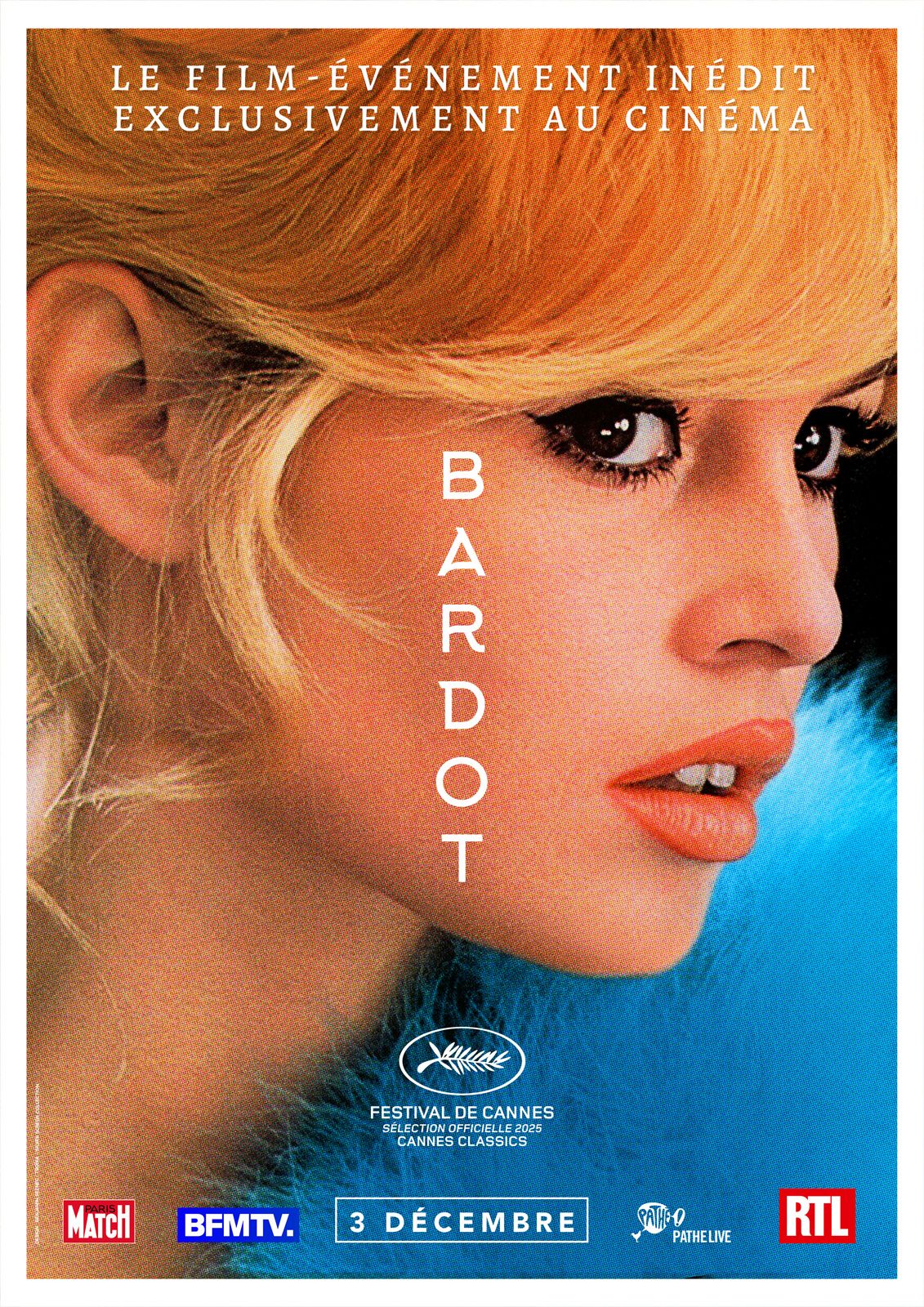

Bardot (2025): Light, Scars and Rebirth

Directed by: Elora Thévenet and Alain Berliner

Produced by: Nicolas Bary – TimpelPictures

Runtime: 1h30

Selection: Cannes Classics 2025

Music: Laurent Perez del Mar, Madame Monsieur, Selah Sue, Ibrahim Maalouf

The rediscovered voice

There are many films about Bardot, but very few that let her speak. This one does.

Elora Thévenet and Alain Berliner chose to give Brigitte Bardot her own voice again. At 90, she speaks from her home in La Madrague, where she has lived in seclusion for half a century. What she says moves us. She doesn’t try to charm or defend herself. She remembers.

The documentary draws on rich material: previously unseen archives, some provided by her family, others retrieved from magazines, INA, and Paris Match. These images, often known only through fragments, are finally placed in their full context. They tell the story of how a myth was built—and how it broke down.

Living under the lens

The opening sequences recall the media frenzy of the 1960s: Bardot surrounded by photographers, chased through streets, observed, reduced to a symbol. The film shows what this constant exposure did to her—fear, loss of privacy, exhaustion. Bardot mentions her suicide attempts without melodrama. She says it quietly, almost reluctantly. You understand how much the violence of the gaze, of judgment, of her time, marked this woman who wanted freedom yet was trapped in her own image.

Thévenet and Berliner film this contradiction without trying to solve it. They let it exist. The result is often deeply affecting.

Images and their counterpoint

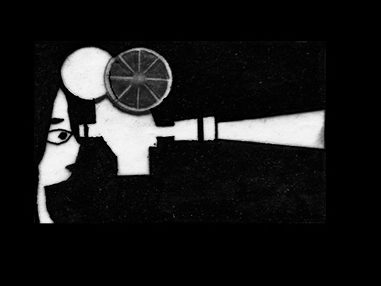

The documentary doesn’t just pile up footage—it confronts it with animated imagery, drawn fragments and digital textures created by Gilles Pointeau. These moments express what the camera never captured: fear, solitude, childhood memories, the hidden side of the smile.

This choice gives the film breathing space. It turns biography into something tactile and intimate, halfway between recollection and dream.

Music as another memory

The soundtrack is essential. Laurent Perez del Mar composed the instrumental score, while Madame Monsieur, Selah Sue, Albin de la Simone, and Alice on the Roof revisit Bardot’s iconic songs. The result is remarkable.

These reinterpretations don’t try to imitate Bardot, but to make her resonate. “Harley Davidson” becomes an electric prayer. “Bonnie and Clyde,” a bittersweet exchange. And “Je t’aime moi non plus,” under Ibrahim Maalouf’s trumpet, turns into a wordless, almost aching song.

The music runs through the film like a second narrative—one of sound, memory, and melancholy.

From fame to retreat: a different fight

The film’s final act covers the turning point in her life. At 38, Bardot walked away from cinema, refused to return, sold much of her property, and founded the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the Protection of Animals. The film depicts this shift with restraint, free of grand speeches. We simply see her writing letters, feeding her dogs, speaking about animal suffering.

The directors remind us that this choice wasn’t without danger. She was threatened, insulted, ridiculed. But this time, she had found purpose.

“I don’t care if people remember me. I want them to remember the respect owed to animals.” This line, captured in a still shot, closes the film. It’s simple and devastating.

A measured gaze

Where many films get lost between adoration and trial, Bardot finds middle ground. It shows everything—the contradictions, excesses, and flaws, but also the constancy, sincerity, and solitude. And it doesn’t seek approval. It documents.

Elora Thévenet and Alain Berliner’s direction is restrained. No intrusive narration, no commentary. They let the images and Bardot’s voice do the work. That quietness gives the film its strength.

A film about looking

Between the lines, Bardot is less about an actress than about us—about how we look, consume, and sometimes destroy the women we admire. Her story isn’t unique, but it remains emblematic. The film shows how hard it is to be free in a world that still resists women’s freedom.

Why it matters

Because it connects the personal and the political without insisting. Because it reminds us that an icon can be wounded and still stand tall. And because before the myth, there was a person.

Bardot isn’t a perfect film. It’s better than that—it’s honest. You leave it with a mix of tenderness and respect. And with a simple thought: cinema can still repair a little of what it once damaged.